If you’re in 10th grade you would know. Maus: A graphic novel following a survivor of the Holocaust, written by Art Spiegelman. Over decades, it’s drawn controversy as well as critical acclaim— being awarded the 1992 Pulitzer prize. It’s also currently a required reading for all Punahou Sophomores. Although first published in 1980, the book weirdly seems as relevant as ever. Just last month, it topped Amazon’s bestseller list but perhaps not for the reason you expected. On January 10, a Tennessee school board voted to ban/remove Maus from their 8th grade curriculum. The media reacted quickly with headlines from just about every major news source.

I can recall carefully dissecting Maus and writing essays on it only several months ago. When I saw articles with titles such as “Ahead of Holocaust Remembrance Day, banning the book ‘Maus’ is a modern-day tragedy” (NBC), the situation felt relevant to me as a student and as a reader.

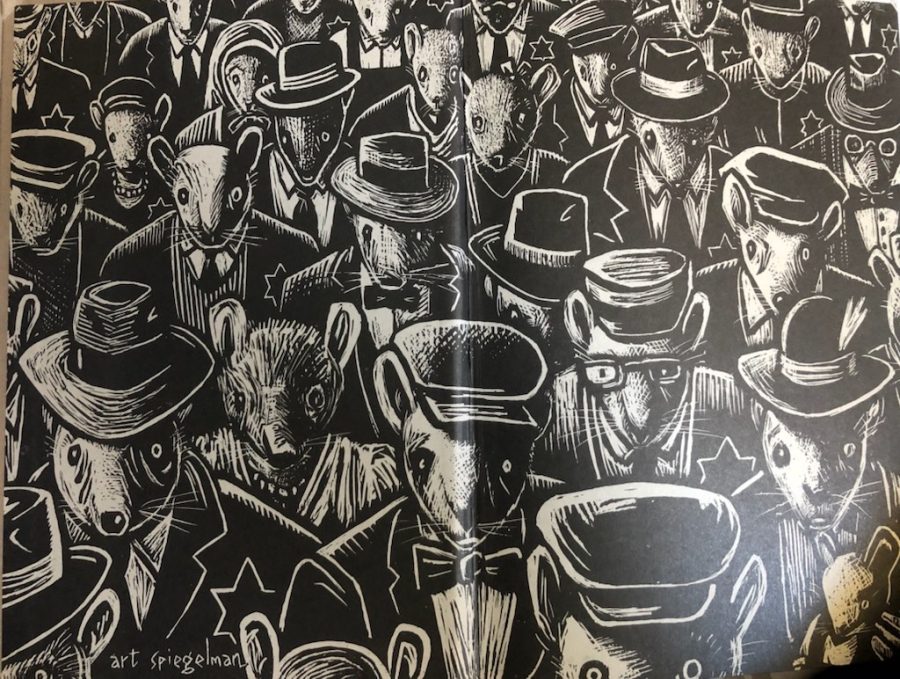

I still remember holding discussions with classmates about how the author chose to write the book. We posed questions: Why did Spigelman choose to depict the characters as animals? Why draw the concentration camp bleeding across the page rather than confined to a box? I even wrote a moral dilemma paper on the author’s father and Holocaust survivor asking, “Should we feel Sympathy for Vladek?”

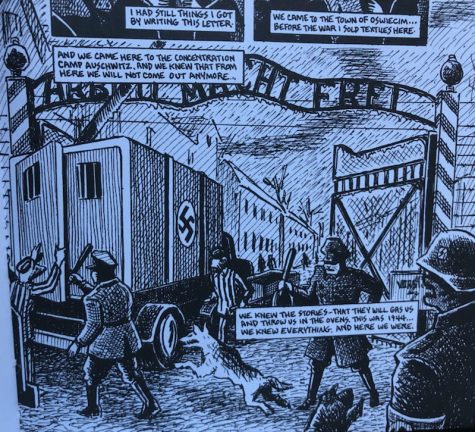

Maus has 3 intertwining timelines—part of the reason why it’s such an indelible story. One follows Vladek through the Holocaust; from his ordeals avoiding persecution to vigilantly trying to survive the concentration camps. The second is Art interviewing his father, illustrating the still all-consuming effects of the war almost 40 years after.

The final timeline is made up of flashes from when the story was being written. They all tie seamlessly together in a finale. The author draws a happy ending of when Vladek and his wife Anja are reunited at the end of the war. Vladek, bedridden, finishes telling Artie, “More I don’t need to tell you. We were both very happy, and lived happy, happy ever after. So…let’s stop, please, your tape recorder…” The page ends with a tombstone of Vladek and Anja Spiegelman, and at the very bottom, the date from Maus was first conceived to when it was finished in its entirety, 1978-1991.

This shows Maus is a story that makes it possible for people to understand past tragedies. While true of other novels, clearly, Maus is an exceptional example. It’s known as a metafiction—a story that comments on itself—we see (literally) how Art felt about hearing and writing his father’s story as well as Vladek telling the actual story of the Holocaust.

We witness someone who doesn’t understand what his father went through. In the book, the author’s character even says, “I know this is insane, but I somehow wish I had been in Auschwitz with my parents so I could really know what they lived through! …I guess it’s some kind of guilt about having had an easier life than they did.” This dialogue lets us relate to Art’s character and feel like we do have a part to play in this story despite only being spectators. It makes sense to me why Punahou decided to include this book as a part of our 10th grade curriculum.

Then why was Maus banned? Was it because their Tennessee school has different values than Punahou or are 8th graders simply too young? The school board’s representative said in defense to the backlash that they “do not diminish the value of Maus as an impactful and meaningful piece of literature.”

The board declared that their reasons for removing the book were the curse words used in the book as well as the author depicting some characters as being nude. They were first planning on redacting the more obscene parts before they unanimously decided to jettison the book from their curriculum. During the board meeting a member of the board, Tony Allman, also reasoned, “It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy,” which became a controversial statement.

In an interview with CNN, Art Spigelman, the author, responded saying he was totally baffled at first, and then tried to really comprehend why, starting to conclude that what happened was mostly “myopic.” They were meticulously focused on only the swear words and nudity; he expressed to us that they’re missing the point. Whether it’s reasonable to remove Maus from an 8th grader’s required reading list is debatable (explanation why later), but the story has gone viral.

Topping headlines, a book written in the 1980’s based on events in the 1940’s comes back into a bright spotlight here in 2022. The decision to ban Maus brought swift and forceful backlash upon the Tennessee school board with many suggesting ulterior motives besides the ones the school board cited. Some sources imply who they believe is at fault, CNBC said the decision comes at a time when “conservatives target curriculums over teachings about the history of slavery and racism in America.”

In spite of these issues, isn’t it good Maus is back in the spotlight? Even today, this book highlights issues in our society. Despite the fact that the event occurred almost a century ago, it still lets us focus back on one of the most crucial events in human history. Hopefully, a benefit of a lot of media coverage is that we will be vigilant in not letting the Holocaust repeat itself. With few Holocaust survivors remaining, Maus then becomes one of the only firsthand and also secondhand accounts of this event.

To me, it also highlights an issue of disunity and lack of discussion in America. That’s the main problem with social media, isn’t it? I’d compare the news to cyber bullying as there is no face to the names. People are described in vague terms at best: the Democrats, Republicans that we read about in the news, are they real people to you? The conclusions we draw about the lives of those penned in an article. An article written by someone who isn’t directly involved. There are pros and cons to this, but those said conclusions won’t always be accurate. Just in general, you’re left trying to make sense of the news based on limited information. I believe being aware of this is important.

When we read these articles, it’s harder to see the people portrayed in it as real human beings. We can’t look those people in their eyes, can’t feel what they’re feeling, and unfortunately, it’s in many ways easier to make verdicts on and attack that which we cannot see.

They banned a book, and we don’t know exactly why, but this entire situation also shows us the core reason why censorship is bad: we can’t learn from things that are censored. We lose the opportunity to discuss and debate, and we should always be able to give real thought to any issue. And what is the right amount of attention to give to an issue? Not too little and not overboard. All of this is easier to do when you ignore political party lines. Isn’t that how we will make sure egregious history doesn’t repeat?

Maus is not a book that stood out to me because of nudity or curse words. It did, however, have a substantial message. People are allowed to question whether it was right or whether it was terrible to remove Maus from an 8th grader’s curriculum, but this whole controversy isn’t all bad.

Maus remains a time capsule, provocative of moral dilemmas, and those said moral dilemmas deserve discussion and people who are really trying to wrap their head around the issue. People like Spigelman who, at the very least, inspire us to reflect on the problems our society faces now. That’s what being meta is for, right?