The following story is an adaptation of “Chapter II: The Blitz” from “Punahou The War Years 1941-1945” by Charlotte Peabody Dodge. Punahou The War Years 1941-1945. Punahou School, accessed 10/03/2024, https://digitalarchives.punahou.edu/nodes/view/14388

On Sunday morning, Mr. Hubert V. Coryell, head of the junior-level English department at the time, packed his bows, arrows, and targets and headed to archery practice at Kapiolani Park. Later in the day, he heard an announcement on the car radio: “Attention everybody—Pearl Harbor is being bombed by the Japanese. This is not a war game…this is the real McCoy…all service men and defense workers report for duty at once…civilians, go home, get off the streets, keep calm.”

He returned to campus and found people watching from Rocky Hill, huddled in nervous groups, or glued to the radio. There were calls for doctors and nurses and one-way reports from the police. Other than that, only silence accompanied the sight of rising smoke in the west.

Just before noon, fires broke out on McCully Street and Lunalilo Elementary School. Teachers and girls on the upper floors of Castle Hall, which was a dormitory at the time, dragged their mattresses into the basement for the night. The radio blared orders from the military government for a complete blackout at dusk and for all schools to close.

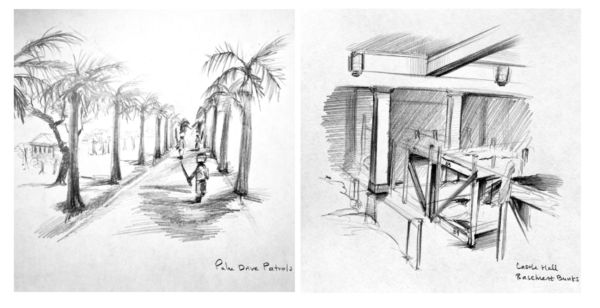

Faculty men and Wilcox Hall boys met and organized a roster of patrol assignments for the night, guarding different areas of the campus from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. They carried ROTC rifles without firing pins, sticks, a length of pipe, and a plumber’s hammer. One teacher, with his two twelve-year-old companions, confronted a military police officer who turned out to be searching for his wife among the refugees, as a few refugees from Hickam Field were residing at Rice Hall.

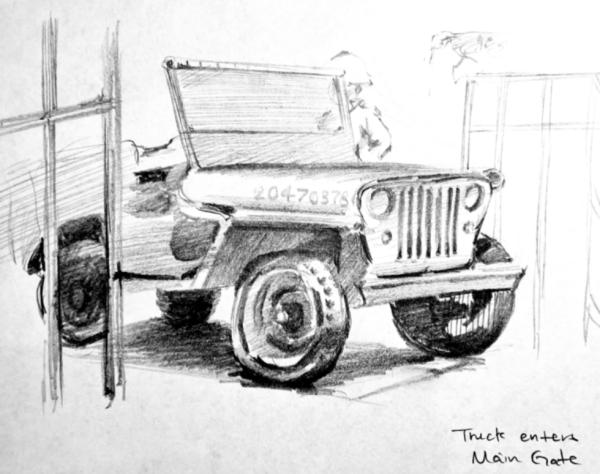

At 9 p.m., an anti-aircraft shell exploded on the lawn between Pauahi Hall and Montague Hall, shattering window glass. At 1:10 a.m., trucks rumbled up to the main gate; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took charge of Cooke Hall, which housed the school switchboard, to use as headquarters. Several officers broke a door and moved furniture while more trucks and hundreds of men poured through the gates.

Just before dawn on December 8th, Cafeteria Manager Mrs. Nina “Peggy” Brown, who was in charge of Dole Hall, received orders to provide breakfast for 750 men. She had to plan in the dark, for she could not even strike a match until daylight. All volunteer helpers, which included teachers, were classified as “kitchen help” and paid at the lowest wage scale, working 8-hour strenuous shifts.

Due to the government’s orders that all Hawai‘i schools be closed, many Punahou students evacuated to the mainland. Students who remained resumed school in early January in makeshift classrooms at Central Union Church and homes. Teachers, rather than students, moved from class to class to save time and gasoline, and students were required to go barefoot to preserve the borrowed floors. “It takes a war to make our dreams come true,” said the first post-Blitz issue of Ka Punahou.

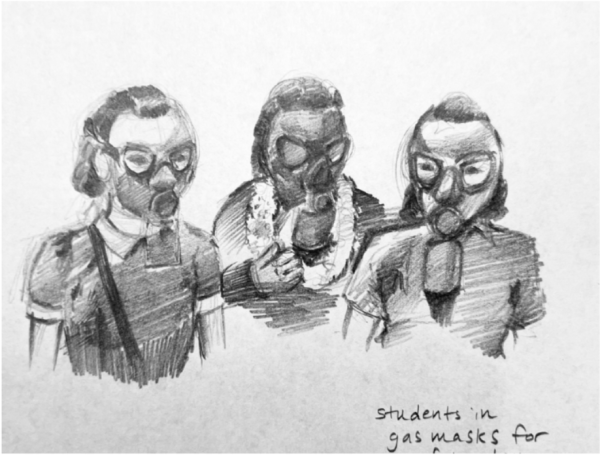

During the exercise periods, boys had to deepen the trenches the army had started. They participated in frequent practice drills, piling into the muddy trenches and staying there until the “all clear” sounded. Girls and female teachers wore slacks daily, and everyone had to carry gas masks.

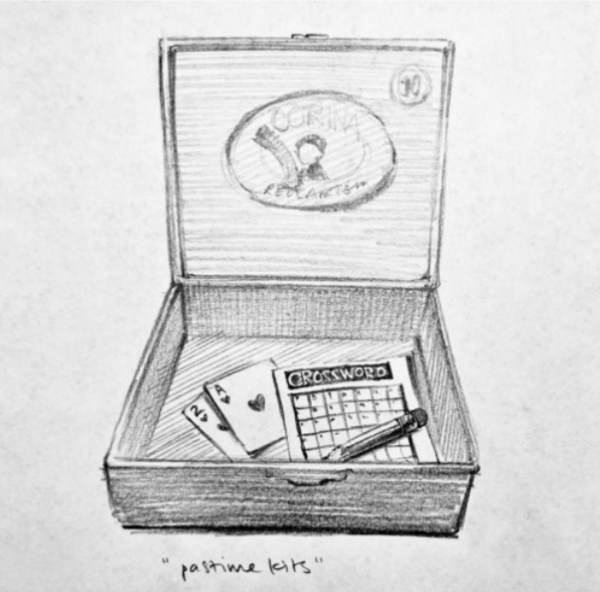

In the summer of 1942, several girls organized a group called Punahou Service, where they devised “pastime kits” made of cigar boxes containing a crossword puzzle, a pencil, a deck of cards, and checkerboards. These were popular with soldiers away from home and in hospitals. The group also printed board games called Salvo made of scrap paper, whose popularity continued after the war.