Our last print edition, Stone & Flow, was about our campus, the place. I was the print editor then, and I had suggested the theme. It seems I am still stuck on the idea—the connection between a physical space and the people who occupy it. But unlike many bound in Stone & Flow, the spaces I wish to present today are not so impersonal (if a place can ever be completely impersonal). This kind of space is free to be molded by the only individual who occupies it. It is an extension of the self.

Often I find myself in a teacher’s office, sitting, waiting, snooping through the periphery of my vision, wondering about their trinkets perched on a windowsill or their posters pinned on a corkboard. I imagine it is a common experience for fellow students. Here, I explore such objects in offices and, through them, learn about the people who they belong to.

Mr. Marshall Comstock

English Teacher

Pauahi Office 201

A few carpeted steps lead up to Mr. Comstock’s office on the second floor of Pauahi. It sits above the Bridge, front and center of the building, as if the room were its heart. The beige ceiling-light, the small window, and bookshelves full on both sides make for a cozy atmosphere. His items are records of his past.

With the room packed full (yet with more cadence than chaos), I wonder where to start poking. I ask for his favorite item. After some contemplation, he half-jokingly chooses his office-mate, Mr. Tancayo-Spielvogel, also an English teacher.

“I used to be in this office kind of alone. … My officemate used to be Mr. Puppione, and he was never here. It was a little lonely, so it’s great to have a lovely officemate.”

He talks of others to whom this office previously belonged. He said “it is an interesting space. … For a while it was known as the ‘goddess office.’ There were primarily female teachers in this space, though, by the time I moved in, they’d been out of it for a while, and it was an older teacher named Ed Moore. He used to yell at the students when they got too loud out there.”

He says he knew that’s not what I meant—he started looking around again. One of his favorites was mounted high, above his tall bookshelf. Deer antlers on wooden planks.

“Those, I found while I was hiking in California, right next to each other. Deer shed their horns, and it’s rare to find a matching pair. But those happened to be right next to each other. So I brought them back, and I put them on that plastic mount thing. So I didn’t kill that deer.”

“My other favorite thing is probably stuff I keep on my window,” he said. His window sill is lined with an assortment of props. Each vie for attention.

- A rusty iron bar, which at a glance looked only like a mechanical part of the window: “There’s a branding iron up here from my parents ranch. … So this was my family’s brand. CV stands for Coyote Valley.”

- A translucent human figure, glowing with sunlight: “So I also have this thing—it’s called the visible man. I got that when I was … I don’t remember, when I was pretty young. It’s like an old anatomy model. And I carted that out with me when I moved here. So little reminders of home, I guess. Those are some of my favorite things.”

- A stripped jam jar that now holds some organic mass. Turns out, they’re wisdom teeth: “My wife said I couldn’t keep them in the house, ‘cause they’re gross.”

- A mysterious ivory animal. It may be one of the oldest things in his office: “I think this was made in the 1920s. A great uncle of mine lived in Africa. He worked there for Standard Oil, and while he was there, he bought these animal trinkets … when he died, I was going through his things, and got some of these. I don’t even know what this animal is called; I’d forgotten.”

“Though, some books in here are probably older than this,” he said. They’re stacked deep and high; layers of it overlapping. The books were perhaps expected from an English teacher—but there were more than just books on the shelves; rows of cameras sit as well.

“These are all my old film cameras. Some of them working, some of them not. I don’t do as much photography as

I’d like to, but I used to. I took some of these photos here.”

Several maps on the walls. More literal representations of homes. Above a collection of black-and-white portraits of his writing teachers, is a map of his birthplace in Lake County, California, dating to 1880, found in a bookstore for 15 bucks.

Another map on the adjacent wall for the place where he grew up. He says, “This is a copy of it, but it’s a map that my great-great-uncle drew of the place in like 1950? I think he drew that? His name was also Marshall Comstock, though he went by Marsh. I never met him. He died young—he was a heavy smoker and he died of lung cancer when he was maybe 38.”

I asked, do you miss your home?

“Yeah, I do. We go back every summer. It’s nice to be able to go back.”

Ms. Lara Cowell

English Teacher

Cooke Hall 125

Ms. Cowell’s office teems with gifts from students, friends, and family. Some traveled far, sent by post or hand-delivered from various reaches of the world. For instance, a student who traveled through the Appalachian Trail sent postcards … from the trail.

“[At some point], he didn’t actually have postcards, so there was something that was cut out of a cereal box and he put stamps on it, mailed it to me, and it actually got to Hawai‘i.”

I was most curious about two blue, red, and pink feet-shaped fabric plates flanking her office entrance. They were gifts, too.

“These are interesting. These are one of the weirdest gifts I ever got. I had a student that was from mainland China. I think these are actually supposed to be posted outside your door—but they’re basically, in Chinese characters, wishing good fortune (吉祥如意, “Good luck according to one’s wishes”). I don’t know if they’re supposed to be for New Year’s, or what.”

Many other gifts were created for or were inspired by the classes she teaches and taught. Most reference A Midsummer Night’s Dream. For instance, a Magic: the Gathering card, “Moon Sprite,” was given by a seventh grade student who had played the mischievous fairy Puck. Sun-bleached and precious-small, it seemed almost hidden among louder colors on the corkboard wall. Printed on it is Puck’s line, “I am that merry wanderer of the night.” And there are props and costumes. One wall wears a cardboard donkey mask.

“This is actually from a student of mine who played Bottom who gets turned into a donkey. Right behind you is a wall with a hole in it, also from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The feather boa behind you, the pink one, is from a character that’s called Thisbe. There’s a character named Francis Flute—somebody that’s very macho, a young teenager—and he gets forced into playing the girl [Thisbe] in this play [Pyramus and Thisbe, a play within the play] … and he says ‘Oh, faith, let me not play a woman,’ but by the time he performs the play, he’s all like, excited about being Thisbe, and he glams up and this [feather boa] is like a nice little feminine touch.”

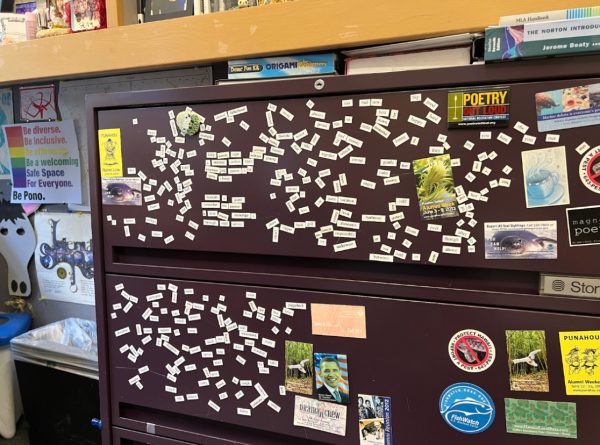

Tucked under the bookshelf is a drawer donning many magnets. Some decorative, but most for magnetic poems, like the ones on fridges. For students who visit her office, they encourage experimentation with language.

“I think there’s something that’s kind of fun about the idea of being playful with language and thinking about them not for grades, not for assignments, but thinking about it as a game … being creative with them. I think it’s something that would be inspirational, something that I hope I do in teaching.”

“I think there’s something that’s kind of fun about the idea of being playful with language and thinking about them not for grades, not for assignments, but thinking about it as a game … being creative with them. I think it’s something that would be inspirational, something that I hope I do in teaching.”

“This office, in a way, I think of it almost as a shrine to things that I value, and also to tchotchkes and little gifts that have been presented from students along the way.”

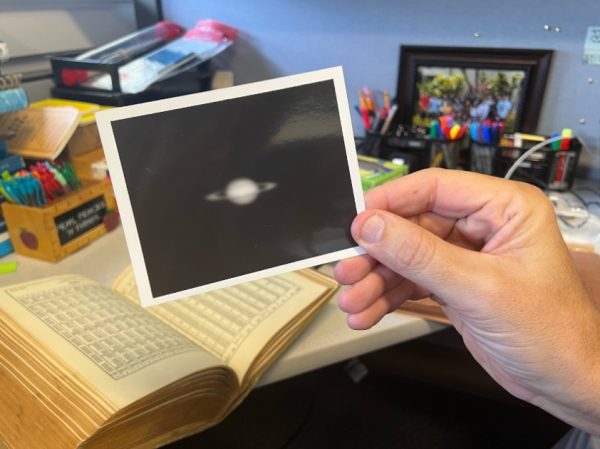

Mr. Adam Jenkins

Physics Teacher

M207 N2

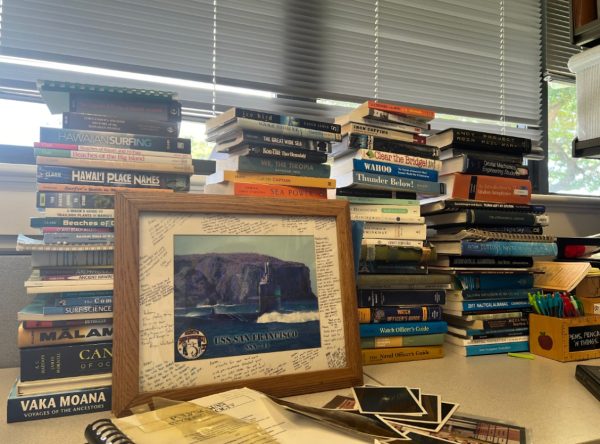

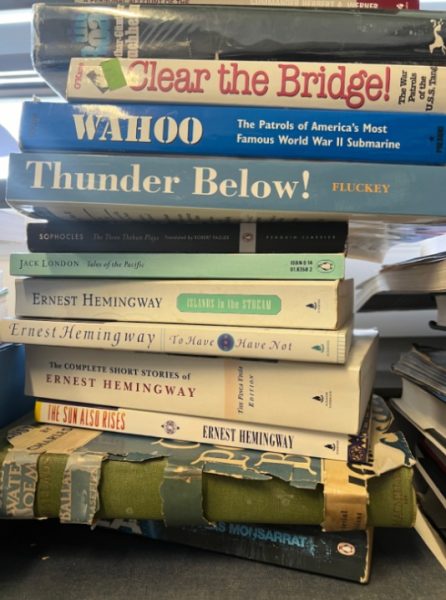

I must be honest—the offices of humanities teachers tend to be more exciting than those of STEM teachers, but this one is an exception. In my memory, Mr. Jenkins’ office has always been colored by shades of blue. Perhaps what’s capturing my attention is the towering wall of ocean-themed book-stacks occupying half his desk.

“I got a lot of books. I have a hard time letting go of books.”

Even many of his fictions, stacked on top of officer’s manuals, feature the ocean. Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, for one.

“I thought it [The Old Man and the Sea] was fundamentally sad. He gives his all fighting this fish, and then he loses it to sharks. So he went through this epic battle, trying to feed his family, and it was all for naught.”

His favorites: For fiction, The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat. (“It’s about World War II, but it’s fictional.”) For Non-fiction, We the Navigators by David Lewis. (“Got me interested in Polynesian navigation. Not exclusively [about] Polynesian, just traditional, non-instrument voyaging.”)

Curiously, he was born in Missouri, a landlocked state. How did he become interested in the deep blue?

“I got into Polynesian voyaging after moving to Hawai‘i, and then surfing. I just realized I was interested in the ocean. Decided to study oceanography.”

He shares yet farther roots: “I was interested in the Navy. … The submarine I was on in the Navy suffered a pretty bad accident related to navigation—it ran into an uncharted sea mount. It ran into a mount and killed one kid, hurt a lot of other sailors on board. And, evidently—I didn’t know this at the time—we know the surface of the moon better than the sea floor of the Earth. I would guess that statement is true today. We don’t have the sea floor mapped as well as we have Mars mapped.”

He points to a comb-bound volume sandwiched in the first pile. I help him take it out, careful not to topple all the others which were resting on top.

“This is the crew manual for Hōkūleʻa. 2014 or so, they started the world wide voyage. Before that, they were training up volunteers, and I got to help teach seamanship, sailing, and a little bit of navigation to new volunteers. … I learned how to sail on western sailboats in the Navy. In 2009, I took Kaʻiulani Murphy’s course in Polynesian voyaging at Windward Community College. For the lab, she said ‘ok, we’re going to go down and re-rig Hōkūleʻa.’ … If you did enough volunteer labor, a captain would start inviting you to sail, so I got to sail under her. … Mostly, I knew how to do the electrical work. Even though they’re replicas of traditional canoes, they have to have running lights and radios to meet Coast Guard rules. I knew how to fix that stuff, and nobody else was interested in fixing it. So that was sort of my niche on board.”

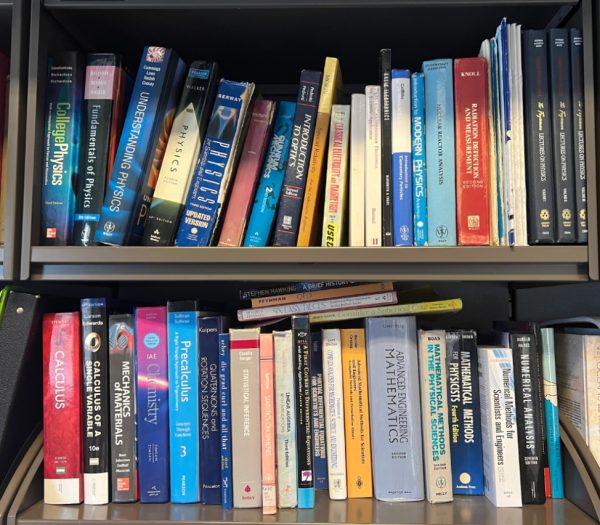

Other books from his impressive collection live on high shelves in more organized rows (though some are still sitting sideways). Weighty textbooks. Many are from when he was in school; undergraduate and graduate. They’re all math and physics—except the newest addition, Zumdahl’s Chemistry. Inspired by a chemistry teacher, he says.

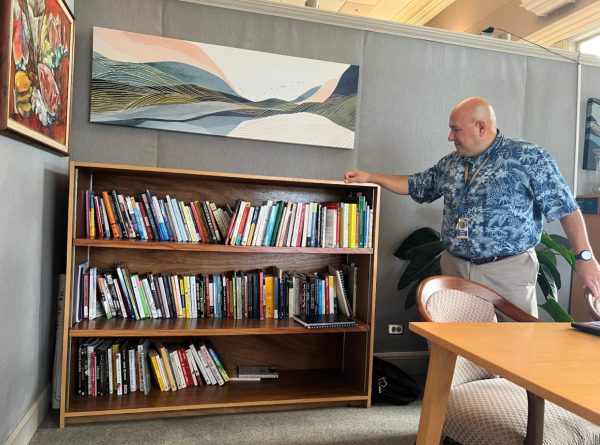

Mr. Gustavo Carrera

Academy Principal

Mr. Carrera’s office sits right near the entrance of Cooke Hall. A fancy plaque with his name and the school seal marks the door. Despite the intimidating connotations that go along with the “principal’s office,” Mr. Carrera makes his space as welcoming as possible. A large desk with chairs around all sides is anchored at the center of the room. On the desk, his cup, notebook, laptop are arranged as if he were sitting facing the windows looking onto the quad just moments before. When he first moved in, he arranged the desk to stand against the windows, like a barrier between the occupant and a guest.

“I did not like that feel at all. It’s not inviting. This feels nicer. I can sit with someone and have a little chat. I love the fact that I can look onto the quad and see all the students.”

I shared with him the thought behind this story—I wanted to explore the idea that someone can express themselves with their space.

“I agree with you. I think that you can communicate things about yourself by the way you dress, by the space you inhabit, in addition to the words you use and the behaviors you engage in.”

The “Be Pono” poster may be one of the very first things a guest notices upon entering Mr. Carrera’s office. Pinned to the right of his PC monitor is an A3 print-out of the school mission.

“I really think [things in an office] matter. For instance, I chose that poster very purposefully. To communicate that this is a safe space for the LGBTAQ+ community. I think it is the first thing I chose for my office, and it matters for this purpose. Having the school mission also conveys the same thing. … I want everybody to know that the school mission matters to me. And I didn’t just put it in a place where people can see it, but it is in a place where people can see that I look at it..”

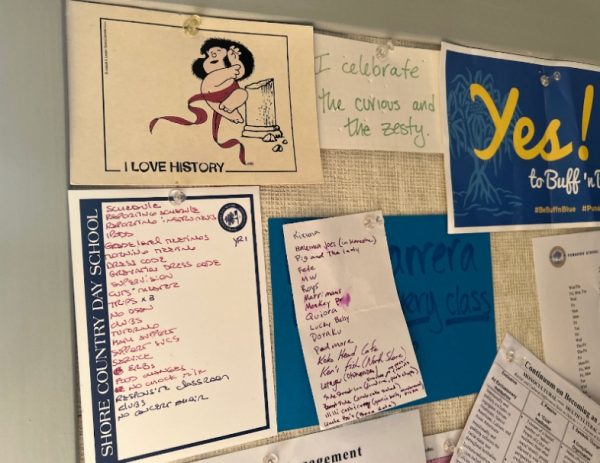

His corner features a standing desk, between the windows. This space seemed to contrast the impersonal versatility of the large centered desk. Next to his work desk is a corkboard with a miscellany of overlapping papers; drawings by children, directories, letters, postcards, pictures.

“I have things that I’ve had for a long time. Emelia is my older daughter, she is 26 years old. She made this when she was in pre-K. They’ve been in every office I’ve ever had. I really like them and I take them wherever I go.” He gingerly unpins the artwork to hold it closer, then another.

“This is by my younger daughter. She drew this during the pandemic.”

A paper-cutout girl wears a green paper-cutout mask.

“This one here—you can also see it’s been in a bunch of offices—this was given to me by the division director, the principal, at another school. Basically it is a quotation of something I said. He thought it was funny, so he put it on a notecard and gave it to me.” Many pin holes decorate the notcard. It reads, in light green ink, ‘I celebrate the curious and the zesty.’

“This one here, ‘I LOVE HISTORY,’ was given to me by my closest friend, she is currently a professor … She sent this to me from Italy … Mafalda, this particular character, is from an Argentine comic strip.”

“The deans gave me a list of different restaurants to try, so I put it there. Because why not.” I might try them myself!

We move from the corkboard to a wooden cabinet. On one end of its shelf, a children’s book leans so that its front cover faces outward. The title reads, If I Ran the School, by Bruce Lansky.

“I got it during Carnival, at white elephant. I saw it and thought, ‘ooh! Let’s buy that one.’”

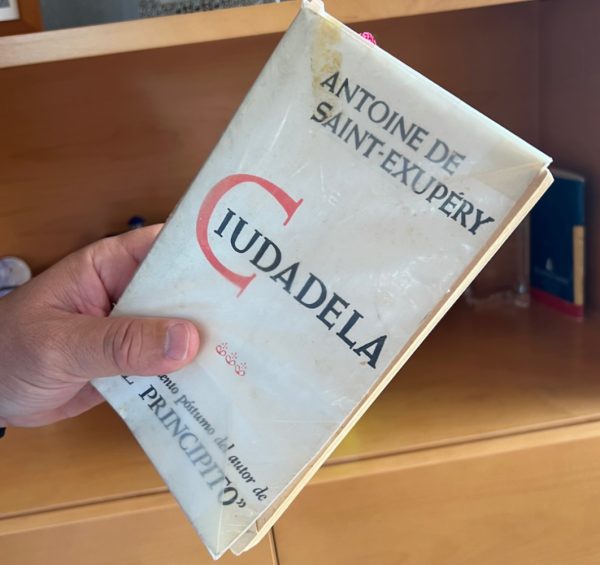

“The Constitution. Big fan.” Mr. Carrera was a US history teacher before he was principal. Next to it, an aging copy of Ciudadela (The Wisdom of the Sands in English) by Antoine Saint-Exupéry. “I’m a big fan of Saint-Exupéry, the guy who wrote The Little Prince. These are some of his posthumous writings. I keep it in mind a lot. I’ve had this book, I don’t know, since I was fifteen?”