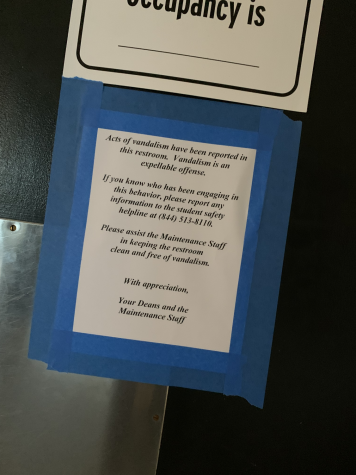

It was nearly the end of September when the signs went up on the doors of restrooms across the Academy and in Case Middle School. “Acts of vandalism have been reported in this restroom,” they read in a neat black serif font. “Vandalism is an expellable offense.” The signs requested that students call the student safety helpline to report people who have engaged in vandalism on campus, and “assist the Maintenance Staff in keeping the restroom clean and free of vandalism.”

What happened?

The short answer: TikTok. The uptick in campus vandalism appears to have been a result of the “devious lick” challenge. This social media phenomenon led students around the world to record video while stealing items from their schools and upload it to the popular app, usually with a remix of the song Ski Ski BasedGod by rapper Lil B playing in the background. Many schools reported experiencing serious vandalism and theft as a result of the challenge. The Hawaii State Department of Education sent out a letter to parents and guardians that described the challenge as “harmful and destructive […] serious offenses that can lead to severe disciplinary consequences,” and asked families to tell their children about “the serious nature of these challenges and the repercussions that can result from participating.”

According to Academy Assistant Principal James Kakos, the situation at Punahou was less serious. Kakos explained that maintenance staff and the school administration noticed an increase in vandalism during September in both the Academy and the middle school, but that there were still only a few instances. Most involved soap dispensers in the bathrooms: students would damage the dispensers or the bags of soap they contain, or remove the bags entirely. This led to soap on the floor, which is a safety hazard and takes a long time for maintenance staff to clean up. While concerning and frustrating to the school administration, these acts of vandalism didn’t quite rise to the level of those seen in other schools both locally and across the United States.

Kakos shared that he considered whether Punahou should send out a letter to the school community after seeing the one from the Department of Education, but he and other administrators decided against it, not believing that the cases were “frequent or egregious enough” to warrant such an action. Similarly, upon learning that other schools had shut down their bathrooms in response to the rise in vandalism, they declined to follow suit. Instead, signs were posted and the Academy Deans reminded students that theft and vandalism would result in serious consequences – and the vandalism stopped.

Kakos emphasized that the problem never went beyond a few isolated incidents. “To me, that’s the headline,” he said. “These things happen, but overall our community is awesome. I’m grateful that the majority of our community did not buy into these challenges that don’t align with our code of conduct or the expectations we have.”

While the short-term issue seems to have passed, the circumstances in which these “devious licks” took place are tied to bigger questions about the wellbeing of students at Punahou and everywhere else. “I think this challenge shows the power of social media,” Kakos noted, explaining that if content on social media can cause teens to engage in vandalism it may also be able to lead them toward even more harmful or unsafe activities. His concerns aren’t unfounded. Past “challenges” on social media have led teens to consume laundry detergent and climb on unstable piles of plastic milk crates. As The Washington Post reported, the “devious lick” challenge fits into the same category of trends.

Teen engagement in unsafe internet challenges has become a popular research subject, as one recent literature review in the journal Current Opinion in Pediatrics found. Many researchers have approached the phenomenon as an example of irrational behavior by teenagers, but this perspective is not universal. Disturbingly, one paper titled The Rationality of Literal Tide Pod Consumption contains an economist’s argument that participation in the “Tide Pod Challenge” (which involved eating pods of laundry detergent) was actually a rational behavior for teens because of the social benefit from engaging in the challenge. The paper pointed out that social expectations and benefits are commonly accepted as a reason for other dangerous behaviors by teens, such as drug use. In simple terms, while social media is responsible for amplifying unsafe challenges, the reason teens choose to engage in them may be much more deeply ingrained in human nature or in the structure of those teens’ social environments. If that’s true, making changes to social media or even getting off it altogether might not be enough to address the spread of dangerous behavior.

“Social media challenges that encourage poor behavior and potential safety risks are likely not going to go away anytime soon,” reflected Kakos. “I think the best approach to addressing these trends is to proactively discuss our community standards of behavior, as well as supporting each other in making the right choices. I’m proud of our efforts to promote these important conversations in our SURF classes, as well as with advisors, deans, and faculty members.” Even if “devious licks” are quickly forgotten by students, their lesson to educators will likely last for many school years to come.